4 KB of love for a 40-years-old aesthetic

Oct 10, 2025

So there I am, casually browsing the latest Unicode updates – just another normal day, right? Definitely not about to start another side project.

While skimming through new character charts, I came across this absolute treasure: the Symbols for Legacy Computing Supplement, released with Unicode 16.0. But before diving into that, it helps to know what came before it.

According to Wikipedia, the Symbols for Legacy Computing block brings together glyphs from a whole range of 1970s–1980s home computers and teletext systems – Amstrad CPC, MSX, Atari ST, ZX81, PETSCII, and plenty more. Think a plethora of line-drawing characters, semigraphics made of funky sextant blocks, and a bunch of otherwise unclassifiable little gems. It's basically a nostalgia‑packed toolkit for recreating the retro terminal aesthetics Unicode didn't know it was missing – until this block arrived. Some highlights:

🮘 🮙 – crisp diagonal stripes

🮰 – a cursor

🯅 🯉 – adorable stick-figure icons

🯰 🯱 🯲 🯳 🯴 🯵 🯶 🯷 🯸 🯹 – segmented digits, straight from a walkman display

🭅 🭆 🭇 🭈 🭉 🭊 🭋 🭓 🭔 🭕 🭘 🭙 🭚 – slopes of any kind imaginable

And just when you think that's comprehensive, the Supplement swoops in and turns the dial to max. It adds even more of everything: expanded box-drawing sets, quirky four-character emoticons, and, hell, even Pac‑Man and Snake glyphs!! Yes, Unicode is now one step closer to becoming its own mini‑arcade.

One set of symbols in particular stands out: the octants, and that's what

this post is going to focus on. Each one can render an 8‑bit value as a tidy

little 2×4 grid – filled blocks for 1s, blank spaces for 0s. The Unicode range is

U+1CD00–U+1CDE5.

If you're expecting it to neatly cover all 256 possibilities up to

U+1CDFF – sorry! The continuity doesn't quite line up. Several pre‑existing

glyphs, like U+2580 UPPER HALF BLOCK ▀, already occupy that conceptual space,

so the octant range leaves some gaps. This means that for all practical

purposes you'll have to keep that mapping hardcoded. But if you're a code

golfer, that might feel less like a setback and more like an invitation.

Anyway, it instantly reminded me of braille patterns, particularly the extended range that lets you combine dots in ways that don't always make linguistic sense, but can still encode an 8‑bit value. That extended braille range has inspired its own small ecosystem of creative misuse, too. One well‑known example is how many installer utilities use those braille characters as makeshift spinners, cycling through patterns to show that something's happening behind the scenes, like so:

⠋ ⠙ ⠹ ⠸ ⠼ ⠴ ⠦ ⠧ ⠇ ⠏

⣾ ⣽ ⣻ ⢿ ⡿ ⣟ ⣯ ⣷

⠋ ⠙ ⠚ ⠞ ⠖ ⠦ ⠴ ⠲ ⠳ ⠓

⢄ ⢂ ⢁ ⡁ ⡈ ⡐ ⡠

⠁ ⠂ ⠄ ⡀ ⢀ ⠠ ⠐ ⠈

⣼ ⣹ ⢻ ⠿ ⡟ ⣏ ⣧ ⣶

⠁ ⠂ ⠄ ⡀ ⡈ ⡐ ⡠ ⣀ ⣁ ⣂ ⣄ ⣌ ⣔ ⣤ ⣥ ⣦ ⣮ ⣶ ⣷ ⣿ ⡿ ⠿ ⢟ ⠟ ⡛ ⠛ ⠫ ⢋ ⠋ ⠍ ⡉ ⠉ ⠑ ⠡ ⢁

⠁ ⠂ ⠄ ⠂

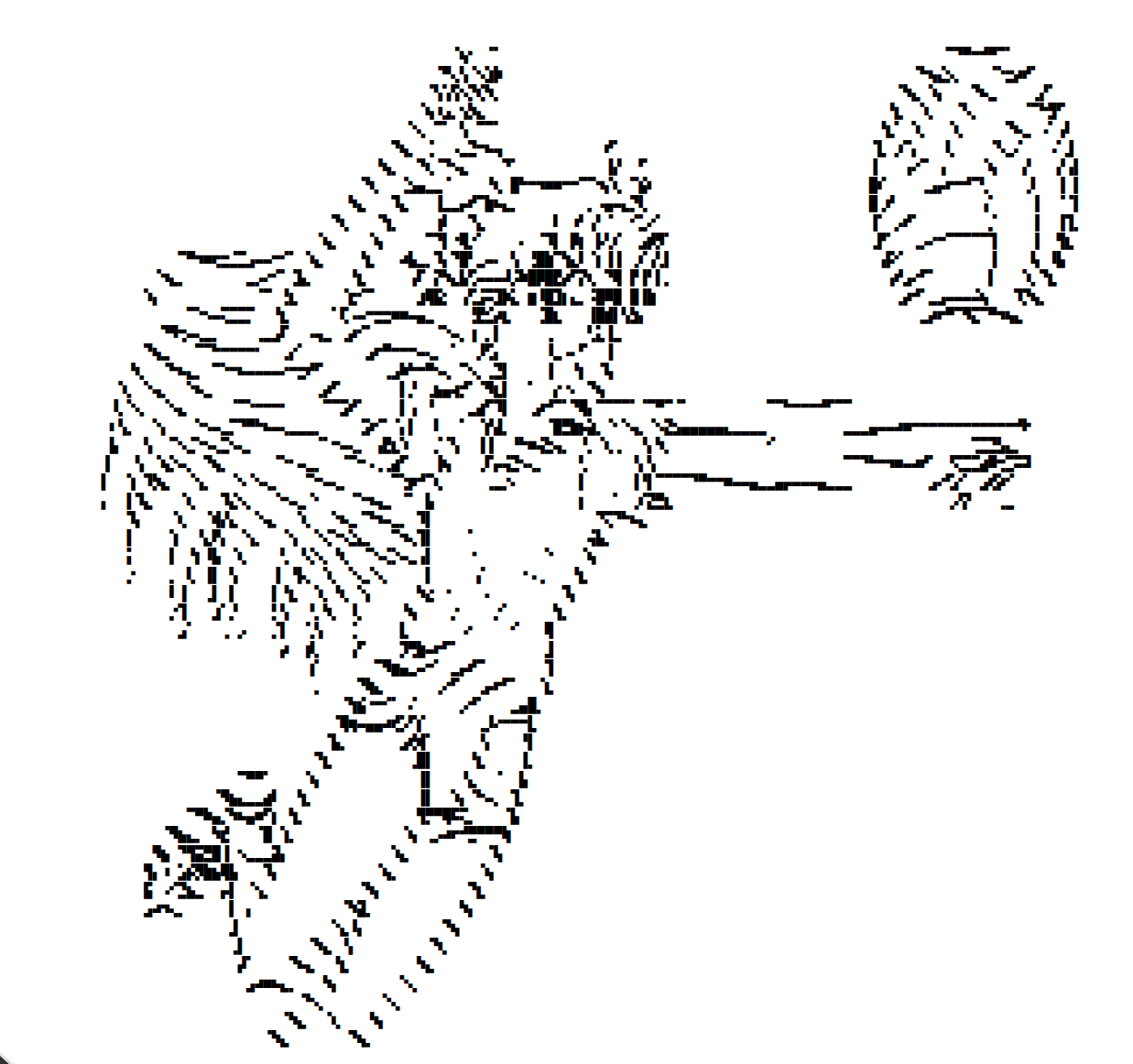

They can even double as tiny pixels, letting you render images directly in the terminal, being surprisingly pretty for low‑resolution art:

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⠀⠀⡀⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡀⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⠀⠀⠀⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⡂⠂⡂⡂⡂⡂⠂⡂⠂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⠂⠂⡂⡂⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⠀⠀⠀⡀⠂⠂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⠀⠂⠂⡀⡪⡪⡪⡂⡂⡂⠂⠂⠂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡀⠀⠀⡂⡂⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⠂⠀⠀⡀⠂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⠀⠀⠂⡢⡪⡪⣪⡪⡂⡂⡂⡂⠀⠂⠀⡂⡂⡂⡂⠂⠂⠂⠂⠂⠀⠀⠀⠈⠢⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡀⠀⠀⠀⡂⡂⡂⡂⡊⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⠂⠂⠂⠀⠀⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠈⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡀⠀⠀⠀⠂⠀⠀⠀⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⠀⠀⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⠀⠀⠀⠀⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠢⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⠀⠀⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⠀⠀⡀⡀⡀⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⡂⡂⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⡂⡂⡪⡂⡂⡀⡀⡀⡀⡀⡂⡀⡂⡂⡂⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠨⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⠀⠀⡂⠀⠀⡀⡀⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡢⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡪⡢⡂⡂⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⡪⡢⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡢⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⠀⠀⠀⠨⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡀⠀⡂⡀⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡪⡊⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡪⡂⡂⡂⡪⡀⠀⠀⠀⡀⡠⡂⡢⡂⡺⡂⡢⡂⡂⡢⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⠀⠀⠈⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⡂⡂⡂⡪⡂⡂⡂⡪⡪⡊⡊⡢⡂⡂⡂⡊⡂⡊⡂⡊⡢⡀⡠⡊⡊⠂⠂⡪⠊⡂⡂⡂⡢⡊⡪⡢⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⠀⠀⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡪⡢⡂⡪⡪⡢⡀⠀⠂⡂⡂⡊⡪⡂⠂⡀⠊⠂⡂⠂⠀⠀⠀⡀⡪⡢⡪⡊⣂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡪⡢⡂⡂⡂⡂⠀⠀⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⡂⡂⡂⡊⡪⡢⡪⡪⡪⣢⣂⡂⡂⡂⡢⡂⡪⡢⡀⡀⠀⠀⠀⠠⡲⠲⡺⡺⡺⡺⡺⡺⡺⡪⡊⡂⡂⡪⡪⡪⡂⡂⡂⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⡂⡂⡂⡊⡪⡪⡊⡊⠚⠺⠊⣺⡪⡊⡊⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡀⡠⡪⡺⠪⡂⠂⡂⡪⡂⡂⡂⡪⡪⡪⡂⡂⡂⡂⡀⠀⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⡂⡪⡪⡂⡀⠂⠂⠊⠊⠂⠂⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⡂⡂⡂⡢⡪⡪⡊⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡀⠂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⡂⡪⡪⡪⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡢⡊⡂⡂⡢⡪⡪⡊⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⡂⡊⡪⡪⡪⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡀⡀⡠⡠⡊⡢⡢⡪⡪⡪⡪⡊⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⡊⡪⡪⡪⡢⡀⡀⠀⠀⠂⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠈⡊⡊⡊⡪⡊⡊⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡪⡢⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⠂⡀⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡀⡂⡂⡂⡂⡪⡢⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡪⡪⡪⡢⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡀⠀⠂⠢⡀⡀⡀⠂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡠⡊⡂⡂⡂⡂⣪⡪⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡊⡪⡪⡪⡢⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡀⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⠀⠀⡀⡀⡀⠪⡂⠂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⠀⠀⠀⣀⡢⡊⡂⡂⡂⡂⣢⡢⡺⡊⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡪⡂⡪⡪⡪⡪⡢⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡀⠂⠂⠀⠀⡀⠂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠠⣺⣢⣲⡺⡊⡂⣢⡢⡲⣪⣪⣺⣺⣺⡂⡂⡢⡂⡂⡂⡪⡢⡪⡪⡪⡪⡪⡢⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⠂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⠀⠀⡀⡂⡂⠀⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⣪⣪⣺⡺⣺⣪⣪⣺⣺⣺⣺⣺⣺⣺⡊⡂⡢⡪⡂⡂⡂⡪⡪⡪⡪⡪⡪⡪⡪⡢⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡀⡂⠂⡂⡂⡂⠠⠂⡀⡀⡀⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡀⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡊⣺⣺⡪⣺⡺⡺⡺⡚⡊⣺⣺⣺⡊⡂⡢⡪⡂⡂⡂⡢⡪⡪⡪⣪⣪⣪⣪⣺⣺⣺⣺⣺⣺⣺⣺⣺⣺⡂⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡂⠀⡀⠂⠀⠀⠀⡂⠢⡊⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡢⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡀⠠⡂⣺⣺⡪⣺⣂⡂⡂⡂⣺⣺⡺⡊⡢⡪⣪⡂⡂⡂⡂⡪⡪⡪⡪⣺⣾⣾⣾⣾⣾⣾⣾⣾⣾⣾⣺⣺⣺⣺⡂⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡀⡀⠀⠀⠀⡂⡂⠀⡂⡀⡢⡢⡂⡂⡊⡊⡊⡂⡢⡊⡂⡂⡂⡂⣺⣢⣺⣺⡪⣺⣺⣢⡂⣺⡺⡺⡪⡪⣪⣺⡪⡂⡂⡂⡢⡪⡪⡪⣺⣺⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣺⣺⣺⣢⡀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⠀⠀⡀⡊⡂⡂⡂⠈⡂⡪⡪⡢⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⡊⡪⡂⣢⣺⣺⣺⣺⣺⣺⣺⡺⡺⡪⡪⣪⣪⣪⣺⣺⣾⡂⡂⡂⡂⡪⡪⡪⡪⣺⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣾⣺⣺⣺⡂⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⡀⠀⠀⠊⠊⠂⠊⡂⡀⡂⡂⡂⡊⡂⠪⡂⡂⡂⣂⣢⡊⣺⣺⣿⣻⡪⣺⡺⡻⣿⣾⣾⣾⣾⣾⣿⣿⣿⣿⡻⡂⡂⡂⡪⡪⡪⡪⡪⣺⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣺⣺⣺⣺⡀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⡢⡀⡊⡂⡂⠀⡂⡂⡂⣺⣺⣾⣾⣿⣿⣺⡊⡂⡂⡂⡊⡺⣺⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⡂⡂⡢⡪⡪⡪⡪⡪⣺⣾⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣾⣺⣺⣺⡂ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠨⣢⡂⡀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠂⠂⠀⡪⡂⡂⡂⣺⣺⣿⣿⣿⣺⣪⡂⡂⡂⡂⡂⣪⣺⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⡊⡂⡢⡪⡪⡪⡪⡪⣪⣺⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣿⣺⣺⣺⣪

Not bad, but the results tend to look a little washed out, as the dots just don't fill much space.

Yeah, by now you can probably see where this is going. Let's see what happens if we re-render the same image with the octants glyphs, and make this lovely Bayer pattern pop:

▂ ███████████ ████████████ ███████████████████ ██████████████████████ ████████████████████████

I think it looks fantastic! And yes, it's just text like any other, which means you can copy and paste it! Go on, try it!

…Yeah. That's where the magic starts to crumble a bit for most. The effect just doesn't survive across platforms: most fonts are missing these glyphs entirely, and the few that have them rarely come pre‑installed on typical OSes or browsers. In fact, this block of Unicode is so obscure that not even Python 3.13 knows about it when you ask for a glyph name:

>>> print(unicodedata.name('\U0001cd00'))

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<python-input-19>", line 1, in <module>

print(unicodedata.name('\U0001cd00'))

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

ValueError: no such name

Still – just look at it! It's too good not to use. That's what gave me the idea of adding an MOTD for my site's landing page, a place to show off some pretty teletext-inspired artwork. I just needed to make sure everyone could actually see it, so I set out to find a good web font with octant support.

The only stylish contender I managed to find was Cascadia Code, Microsoft's open‑source typeface for developers. It was a solid choice: the glyphs rendered perfectly. Alignment, spot‑on. The OFL license let it be freely embedded. It was pretty. And as a bonus, it even ships with those neat Powerline characters for us command line junkies. Good job, Microsoft!

I installed it on the website, coded up the MOTD artworks and for a while, all was well.

Then I stumbled across the 1 KB Club: a hall of fame for sites that load in less than a single kilobyte. Out of curiosity, I ran my own numbers. No chance I'd get anywhere near 1 KB, but under 100 KB felt realistic – after all, no heavy images, minimal markup – I've got to be somewhere under 100 KB, right?

Not even close. The Cascadia Code font alone clocked in at 176 KB.

I know most wouldn't bat an eye at that, but… I did.

"Not on my server", I thought, and so, optimization became the next priority.

My first step was to trim Cascadia Code down to only the characters I thought I'd need. With FontForge (a free and open-source font editor) open, I planned several large deletions, but stopped short. If too much would be gone, the font would cease to serve for ordinary text. Out of caution, I left the accented Latin characters intact, knowing that mixed content or symbolic notes could require them. That restraint left me with a file of about 100 KB – smaller, yet hardly lean.

That's no good. The next logical option was to cut everything except the octant symbols, but that would leave a sad little husk of a font and would feel more like vandalism than a good solution. There's no reason to wrestle with a derivative so badly reduced. Starting a new font from the ground up would be just better and healthier.

Wait – am I really doing this? Making my own font?

Apparently, yeah? It's just a bunch of squares; what could possibly go wrong?

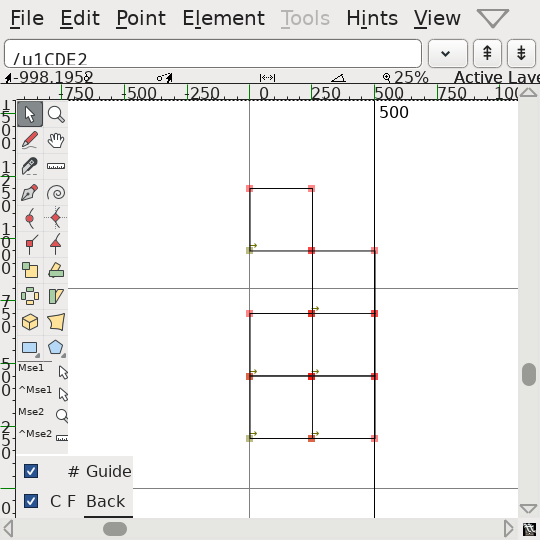

I decided to vibecode this with the AI and the fontforge Python library (yes,

it's scriptable, too!). Given how easy the design is, procedural generation

felt like destiny. Through a bit of tender human-to-LLM hand-holding, I got it

in and it did the job perfectly. Apart from that time when I messed the bit

order:

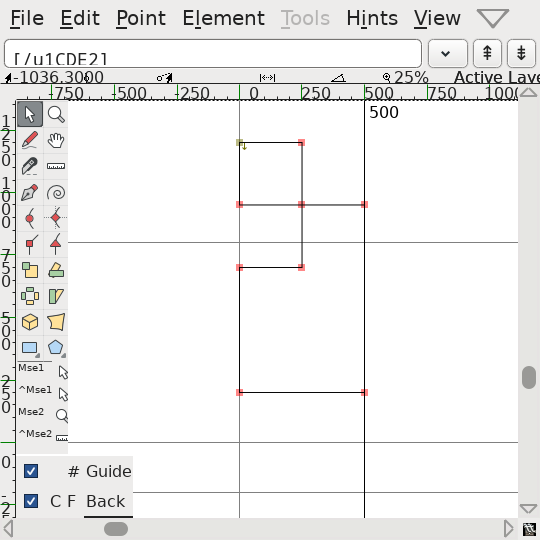

But yes, after correcting everything, the implementation resulted in a 4.2 KB font that worked no worse than Cascadia Code. That was okayish, I guess? Then I opened the file in FontForge and I noticed that there's a lot of duplicate anchor points.

Oh, yeah. We can do way better if we glue the polygons together:

With this strategy, the file ended up at… 4.6 KB. Excuse me?? I guess WOFF compression thought my original pattern of identical squares was a better deal than these respectable polygons.

That little discovery sparked an idea – if WOFF loves repetition so much, why not lean into it? So I drew only eight shapes, one for each "1‑bit" octant, and then composited them to form the rest of the glyphs, treating them like an odd set of accented characters. Combined with trimming a few redundant tables, that cut the file down to 3 988 bytes. Still a long shot from the 1 K Club, but I'll count that as a win.

Technically, this approach could be upgraded to reduce the total references by composing complex characters from larger sub‑glyphs. But at that point, I decided to call it: the font worked, it looked right, and the compression chase had officially reached diminishing returns. Time to ship it rather than shave off another dozen bytes.

Now, some of you might be wondering why I went all‑in on an aesthetic that can't even be copy‑pasted properly, when I could've just mapped my own custom ranges from scratch or hijacked the already‑supported braille symbols and visualized them through a dedicated font. Fair question. But to me, misrepresenting the braille code would feel like cheating, and I'd rather not have that "why does it look so faint when pasted?" moment. I want it to be a little reward for those who do have the right fonts installed – and maybe, one day, for these ranges to catch on enough that we can actually spam IRC and Discord with this stuff, now in far prettier form. 🩷

With all this, my entire page is 81 KB, 51.3 of which are… still fonts. Except this time it's for the title and for the body text. But that's a story for another time.

So that's where we'll leave it: some cool Unicode art, a font you can download here free of charge, and – for the curious – the final version of my font generator packed with every compression attempt, successful or not. Happy hacking!

▂▖ ▄ ▗🮂 ▂🮂🮂▂ 🮂▂▀🮂▂ ▗🮂▗ 🮂▂▖ ▆▆▆▆ █▛██▖▜▀▛ ▂▙█🮂🮂██▜▖▐ ▚█▟▛🮂▘ ▟▌▐▌▐▐▙▝ ▖▌ ▜▞▌▀▝▝▗█ ▗▄▝▟█▟█ ▛ ▟▘ ▟▐ ▝ 🮂▗▄▞ ▌█ ▜▀▆ ▛███ ▐██▖ ▜▙▛██🮂 █▐ ▚█ ▛█🮅 ▖🮂▟ 🮅▖ ▖ ▗▐ ▌ █ 🮅▘ ▂▂ ▞▚ 🮂 🮂 🮂 ▂ ▂🮂▄ ▐▛▌ 🮂▘ 🮂